Every JavaScript project starts ambitiously, trying not to use too many NPM packages along the way. Even with a lot of effort on our side, packages eventually start piling up. package.json gets more lines over time, and package-lock.json makes pull requests look scary with the number of additions or deletions when dependencies are added.

“This is fine” — the team lead says, as other team members nod in agreement. What else are you supposed to do? We are lucky that the JavaScript ecosystem is alive and thriving! We should not be reinventing the wheel every time and trying to solve something that the open-source community has already solved.

👋 As you’re diving into JavaScript dependencies, you might want to dive into AppSignal APM for Node.js as well. We provide you with out-of-the-box support for Node.js Core, Express, Next.js, Apollo Server, node-postgres and node-redis.

Let’s say you want to build a blog and you would like to use Gatsby.js. Try installing it and saving it to your dependencies. Congratulations, you just added 19000 extra dependencies with it. Is this behavior okay? How complex can the JavaScript dependency tree become? How does it turn into a dependency hell? Let’s dive into the details and find out.

What is a JavaScript Package?

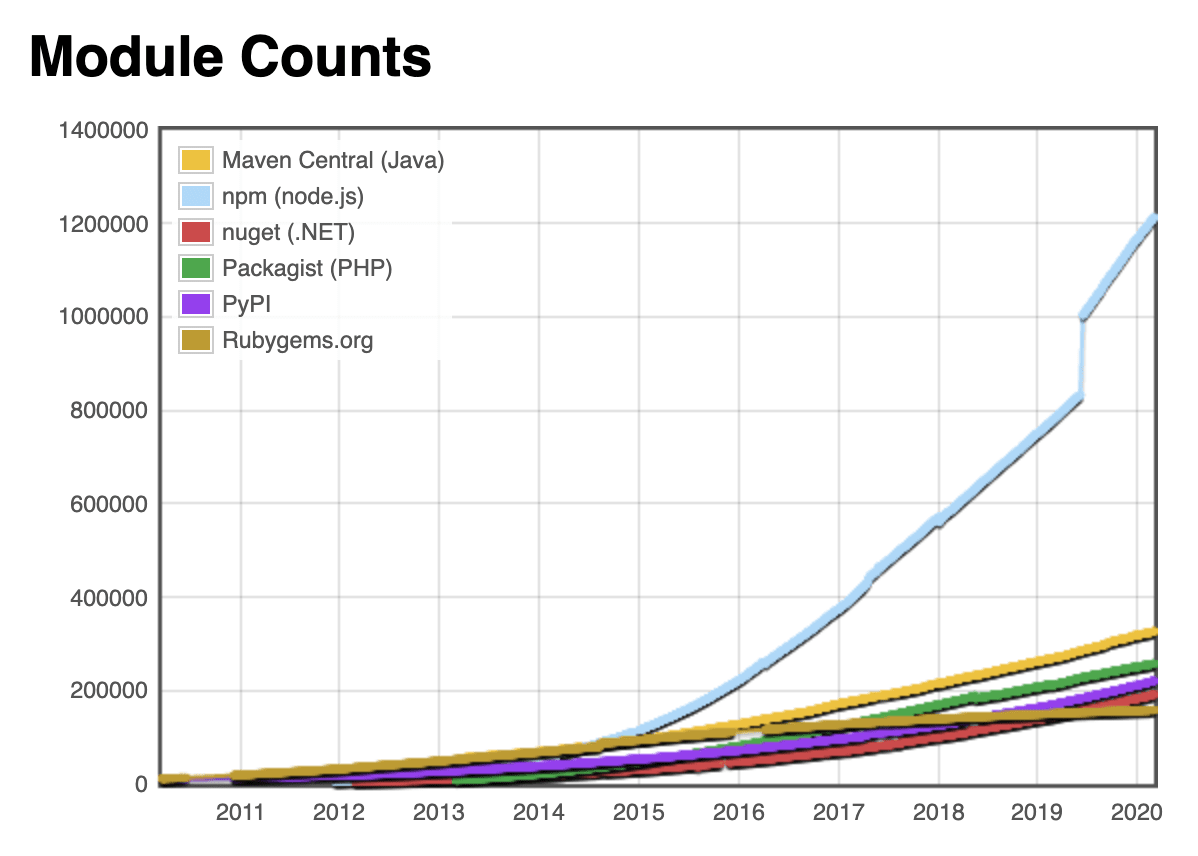

NPM—the Node Package Manager, holds the biggest registry of JavaScript packages in the world! It’s bigger than RubyGems, PyPi, and Maven combined! This is according to the Module Counts website which tracks the number of packages inside the most popular package registries.

That’s a lot of code, you must be thinking. And it is. To have your piece of code become an NPM package, you need a package.json in your project. This way, it becomes a package that you can push to the NPM registry.

What is package.json?

By definition, package.json:

- Lists the packages your project depends on (lists dependencies)

- Specifies versions of a package that your project can use using semantic versioning rules

- Makes your build reproducible, and therefore, easier to share with other developers.

Envision this as a README on steroids. You can define your package dependencies there, write build and test scripts, as well as version your package the way you want and describe it and what it does. We are mostly interested in the ability to specify dependencies inside the package.json.

This already sounds a bit chaotic. Imagine having a package that’s dependant on another package, that’s dependant on another. Yeah, it can go on like that as much as you like. This is the reason why you get 19k extra dependencies when you install a single package—Gatsby.

Types of Dependencies in package.json

To better understand how dependencies accumulate over time, we’ll go through different types of dependencies a project can have. There are several dependencies you can encounter inside package.json:

dependencies— these are the essential dependencies that you rely on and call in your project’s codedevDependencies— these are your development dependencies, for example, a prettier library for formatting codepeerDependencies— if you set a peer dependency in your package.json, you are telling the person who installs your package that they need that dependency with the specified versionoptionalDependencies— these dependencies are optional and failing to install them will not break the installation processbundledDependencies— it’s an array of packages that will come bundled with your package. This is useful when some 3rd party library is not on NPM, or you want to include some of your projects as modules

The Purpose of package-lock.json

We all know that file that always gets lots of additions and deletions in pull requests and we often take it for granted. package-lock.json is automatically generated each time the package.json file or node_modules directory changes. It keeps the exact dependency tree that was generated by the install so that any subsequent installs can generate the identical tree. This solves the problem of me having another version of the dependency, and you have another.

Let’s take a project that has React in its dependencies in package.json. If you go to the package-lock.json you will see something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | "react": { "version": "16.13.0", "resolved": "https://registry.npmjs.org/react/-/react-16.13.0.tgz", "integrity": "sha512-TSavZz2iSLkq5/oiE7gnFzmURKZMltmi193rm5HEoUDAXpzT9Kzw6oNZnGoai/4+fUnm7FqS5dwgUL34TujcWQ==", "requires": { "loose-envify": "^1.1.0", "object-assign": "^4.1.1", "prop-types": "^15.6.2" } } |

package-lock.json is a large list of dependencies in your project. It lists their version, location of the module (URI), a hash that represents the integrity of the module and the packages it requires. If you read on, you can find each entry for every package React requires, and so on. This is where the actual dependency hell lives. It defines everything that your project needs.

Breaking Down Gatsby.js Dependencies

So, how do we end up with 19k dependencies by installing just one? The answer is: dependencies of dependencies. This is what happens when we try to install Gatsby.js:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | $ npm install --save gatsby ... + gatsby@2.19.28 added 1 package from 1 contributor, removed 9 packages, updated 10 packages and audited 19001 packages in 40.382s |

If we look at package.json, there’s only one dependency there. But if we peek into package-lock.json, it’s an almost 14k line monster that just got generated. A more detailed answer to all this lies in the package.json inside the Gatbsy.js GitHub repo. There are a lot of direct dependencies—132 counted by npm. Imagine one of those dependencies having just one other dependency—you just doubled the amount to 264 dependencies. Of course, the real world situation is way different. Each dependency has a lot more than just 1 extra dependency, and the list goes on.

For example, we can try to see how many libraries require lodash.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 | $ npm ls lodash example-js-package@1.0.0 └─┬ gatsby@2.19.28 ├─┬ @babel/core@7.8.6 │ ├─┬ @babel/generator@7.8.6 │ │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped │ ├─┬ @babel/types@7.8.6 │ │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped ├─┬ @babel/traverse@7.8.6 │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped ├─┬ @typescript-eslint/parser@2.22.0 │ └─┬ @typescript-eslint/typescript-estree@2.22.0 │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped ├─┬ babel-preset-gatsby@0.2.29 │ └─┬ @babel/preset-env@7.8.6 │ ├─┬ @babel/plugin-transform-block-scoping@7.8.3 │ │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped │ ├─┬ @babel/plugin-transform-classes@7.8.6 │ │ └─┬ @babel/helper-define-map@7.8.3 │ │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped │ ├─┬ @babel/plugin-transform-modules-amd@7.8.3 │ │ └─┬ @babel/helper-module-transforms@7.8.6 │ │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped │ └─┬ @babel/plugin-transform-sticky-regex@7.8.3 │ └─┬ @babel/helper-regex@7.8.3 │ └── lodash@4.17.15 deduped ... |

Luckily, most of them are using the same version of lodash, which just needs one lodash to install inside node_modules. This is often not the case with real-world production projects. Sometimes, different packages require different versions of other packages. That is why there are tons of jokes on how heavy the node_modules directory is. In our case, it’s not that bad:

1 2 | $ du -sh node_modules 200M node_modules |

200 megabytes is not that bad. I’ve seen it rise above 700 MB easily. If you’re interested in which modules are taking up most of the memory, you can run the following command:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | $ du -sh ./node_modules/* | sort -nr | grep '\dM.*' 17M ./node_modules/rxjs 8.4M ./node_modules/@types 7.4M ./node_modules/core-js 6.8M ./node_modules/@babel 5.4M ./node_modules/gatsby 5.2M ./node_modules/eslint 4.8M ./node_modules/lodash 3.6M ./node_modules/graphql-compose 3.6M ./node_modules/@typescript-eslint 3.5M ./node_modules/webpack 3.4M ./node_modules/moment 3.3M ./node_modules/webpack-dev-server 3.2M ./node_modules/caniuse-lite 3.1M ./node_modules/graphql ... |

Ah, rxjs, you are a sneaky one. One easy command that could help you with the size of node_modules and flattening those dependencies is npm dedup:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | $ npm dedup moved 1 package and audited 18701 packages in 4.622s 51 packages are looking for funding run `npm fund` for details found 0 vulnerabilities |

Deduplication action will try to simplify the structure of the dependency tree by looking for common packages between dependencies and moving them around so that they get reused. This is the case with our example with lodash above. A lot of packages settle on lodash@4.17.15 so there are no other versions of lodash that had to be installed. Of course, we got this from the start because we just installed our dependencies, but if you have been adding dependencies to package.json for a while, consider running npm dedup. If you’re using yarn, you can do yarn dedupe, but there’s no need since this process runs when you yarn install so you’re good to go.

Visualisation of Dependencies

If you’re ever interested in how your project dependencies look like, there are a couple of tools you can use. Some of the ones I’ve used show your, or any other, project dependencies in a different manner.

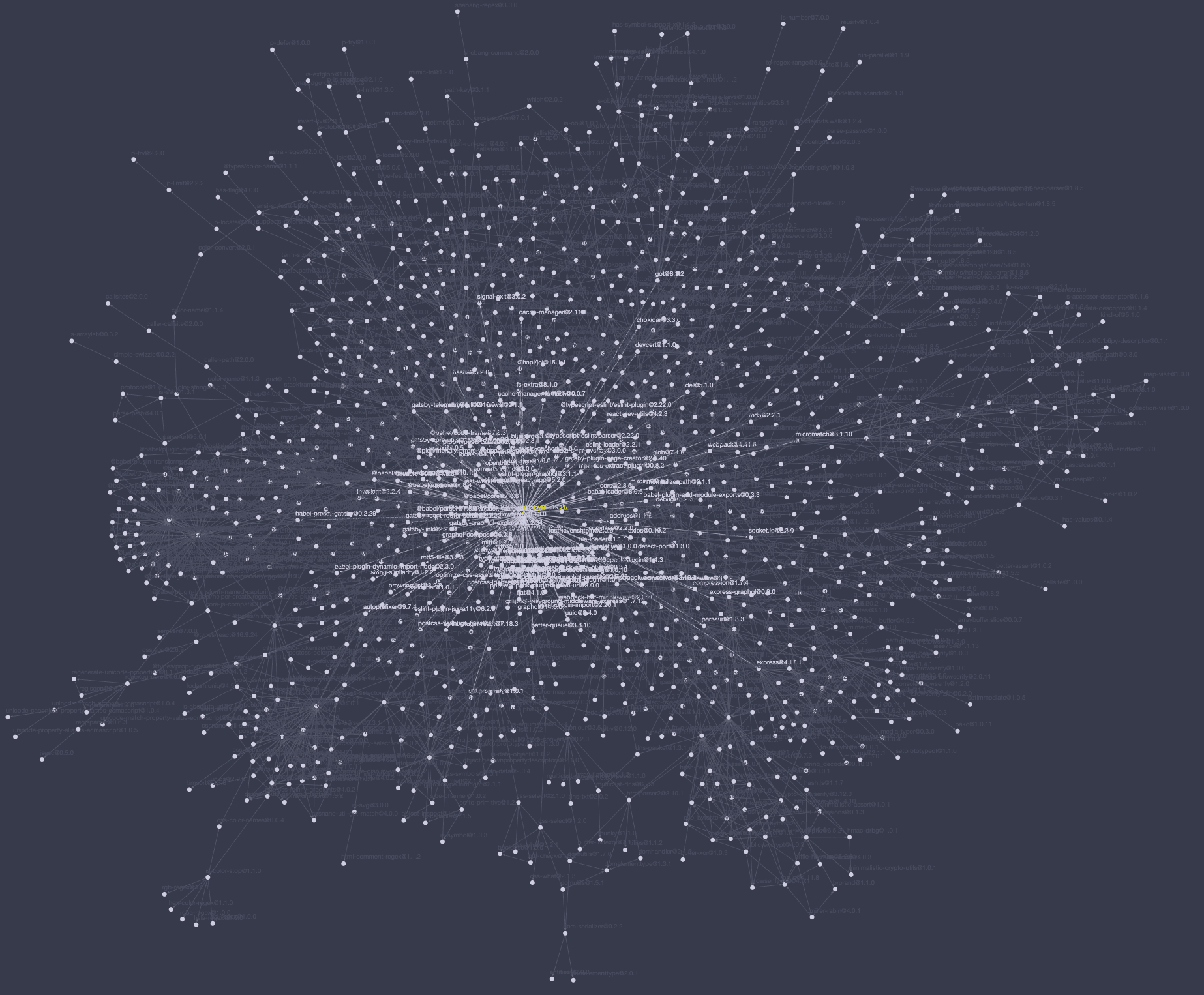

NPM.ANVAKA.COM

Here you can see how each package interconnects, and it all looks like a giant web. This almost broke my browser since Gatsby.js has so many dependencies. Click here to see how Gatsby.js dependencies connect. It can also show it in 3D.

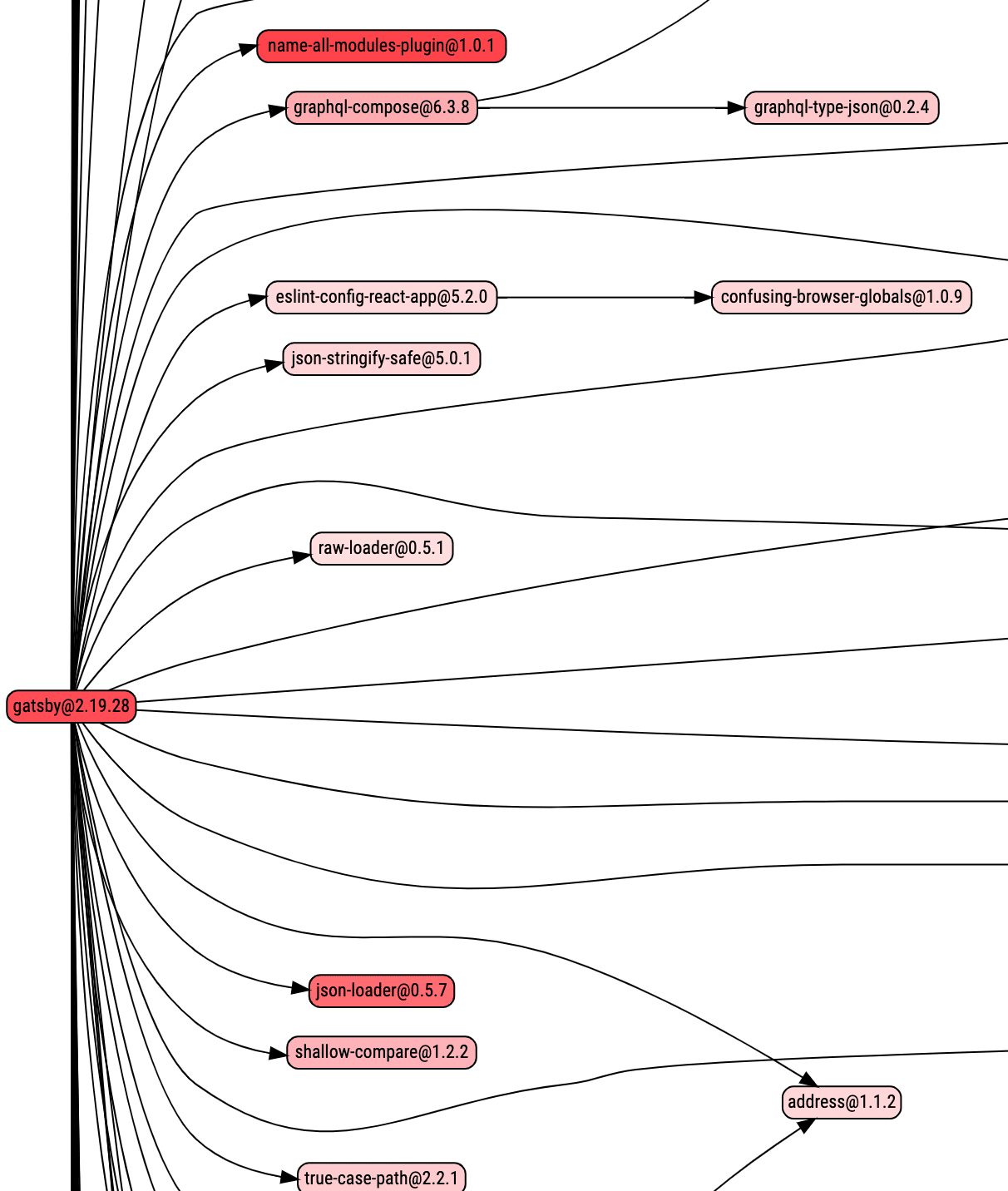

NPM.BROOFA.COM

This is a view of dependencies similar to a flow chart. It gets complicated for Gatsby.js pretty fast if you want to take a look. You can mark each dependency’s npms.io score and it will color them differently based on their score. You can also upload your package.json and have it visualized there.

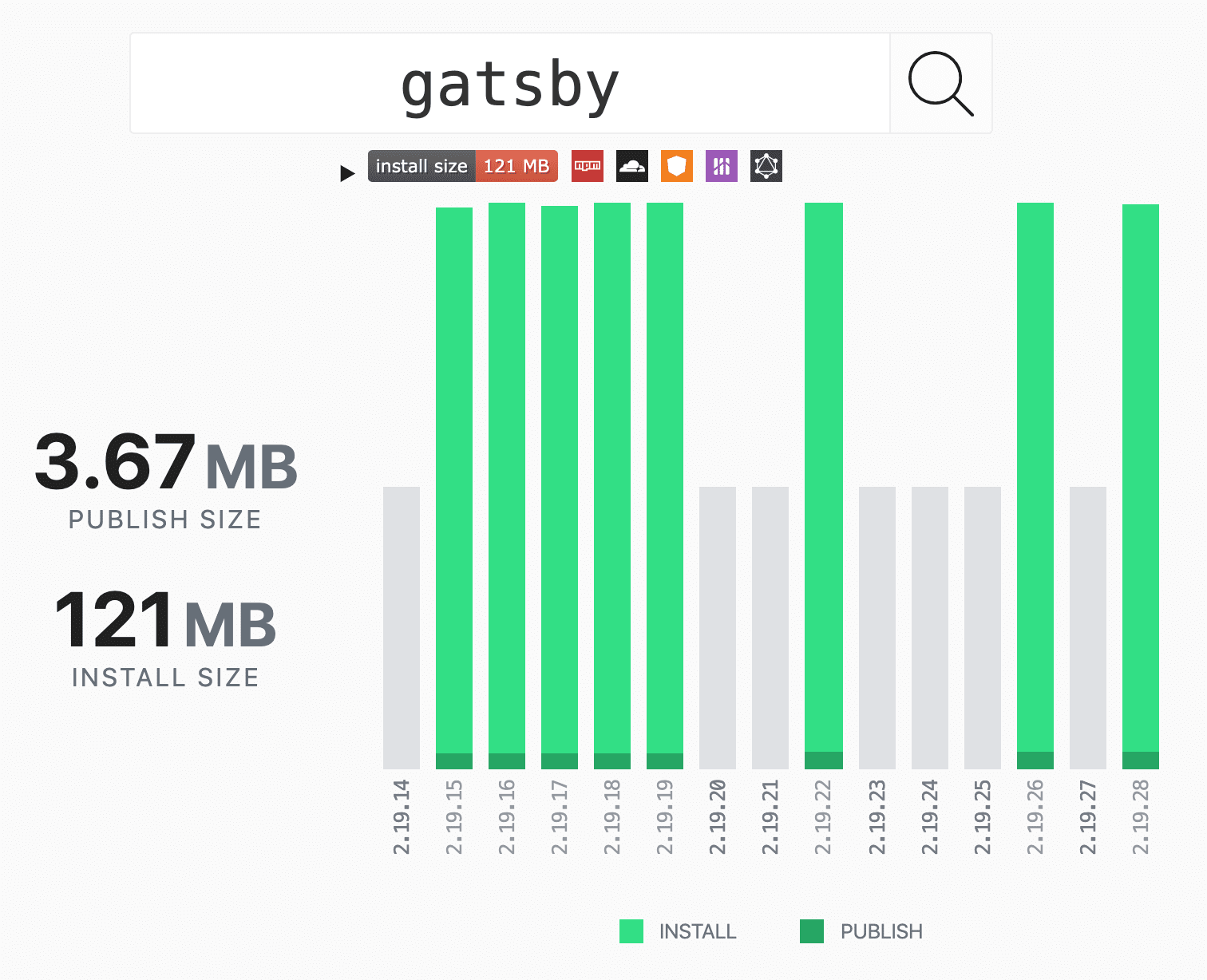

PACKAGE PHOBIA

A great tool if you want to check how much space a package will take before you run npm install. It will show you the publish size at the NPM registry and the size on disk after you install it in your project.

Comments

Post a Comment

Share your thoughts!