Breaking Down Scope, Context, And Closure In JavaScript In Simple Terms.

Breaking Down Scope, Context, And Closure In JavaScript In Simple Terms.

“JavaScript’s global scope is

like a public toilet. You can’t avoid going in there, but try to limit your contact with surfaces when you

do.”

― Dmitry Baranowski

Here’s another (much) more simple article I wrote on the subject:

Answer A closure is a function defined inside another function and has access to its lexical scope even when it is…dev.to

I made this website in support of the article… it links to a navigation page as well as the repo where more examples are kept…

https://scopeclosurecontext.netlify.app/

Prerequisites

- creating and initializing a variable

- creating a function

- invoking a function

- logging to the console

further prerequisites:

Quiz yourself with this website I made:

Vocab (most of these will be detailed many times over in this article!)

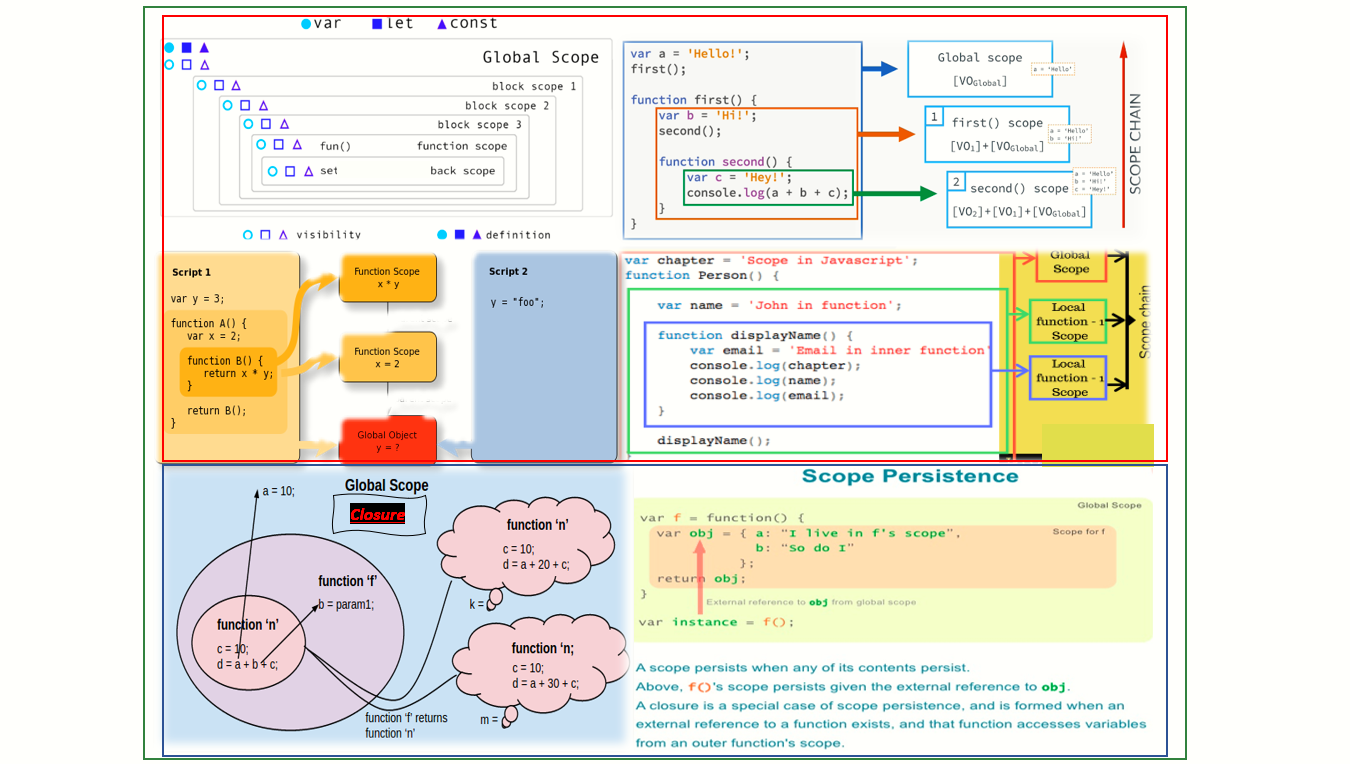

- Scope: “Scope is the set of rules that determines where and how a variable (identifier) can be looked-up.” — Kyle Simpson, You Don’t Know JS: Scope & Closure

- Function Scope: Every variable defined in a function, is available for the entirety of that function.

- Global Scope: “The scope that is visible in all other scopes.” — MDN

- Global Variable: A variable defined at the Global Scope.

- IIFE: Imediatly-Invoked Function Expression — a

function wrapped in

()to create an expression, and immediatly followed by a pair of()to invoke that function imediatly. - Closure: “Closures are functions that refer to independent (free) variables. In other words, the function defined in the closure ‘remembers’ the environment in which it was created.” — MDN

- Variable Shadowing: “occurs when a variable declared within a certain scope … has the same name as a variable declared in an outer scope.” — Wikipedia

- for statement: “The for statement creates a loop that consists of three optional expressions, enclosed in parentheses and separated by semicolons, followed by a statement or a set of statements executed in the loop.” — MDN

- initialization: “An expression (including assignment expressions) or variable declaration. Typically used to initialize a counter variable. This expression may optionally declare new variables with the var keyword. These variables are not local to the loop, i.e. they are in the same scope the for loop is in. The result of this expression is discarded.” — MDN

- condition: “An expression to be evaluated before each loop iteration. If this expression evaluates to true, statement is executed. This conditional test is optional. If omitted, the condition always evaluates to true. If the expression evaluates to false, execution skips to the first expression following the for construct.” — MDN

- final-expression: “An expression to be evaluated at the end of each loop iteration. This occurs before the next evaluation of condition. Generally used to update or increment the counter variable.” — MDN

- statement: “A statement that is executed as long as the condition evaluates to true. To execute multiple statements within the loop, use a block statement ({ … }) to group those statements.” — MDN

- Arrays: “JavaScript arrays are used to store multiple values in a single variable.” — W3Schools

I am going to try something new this article… it’s called spaced repetition.

“Spaced repetition is an evidence-based learning technique that is usually performed with flashcards. Newly introduced and more difficult flashcards are shown more frequently, while older and less difficult flashcards are shown less frequently in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect. The use of spaced repetition has been proven to increase rate of learning.”

CodePen For You To Practice With:

Open it in another tab… it will only display the html file that existed when I pasted it into this article… for access to the JavaScript file and the most up to date html page you need to Open the sandbox… feel free to create a fork of it if you like!

SCOPE:

- The

scopeof a program in JS is the set of variables that are available for use within the program. - Scope in JavaScript defines which variables and functions you have access to, depending on where you are (a physical position) within your code.

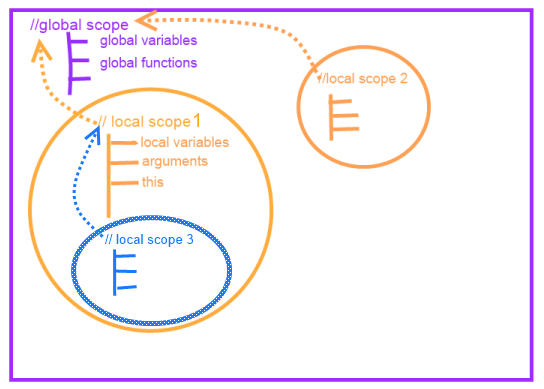

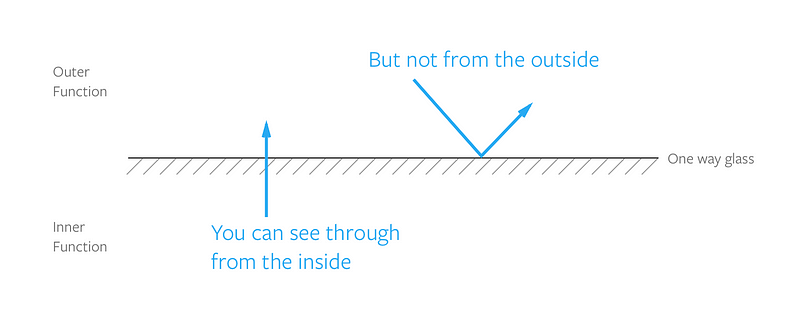

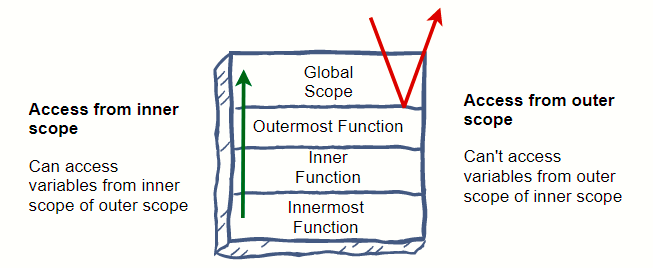

- The current context of execution. The context in which values and expressions are “visible” or can be referenced. If a variable or other expression is not “in the current scope,” then it is unavailable for use. Scopes can also be layered in a hierarchy, so that child scopes have access to parent scopes, but not vice versa.

- A function serves as a closure in JavaScript, and thus creates a scope, so that (for example) a variable defined exclusively within the function cannot be accessed from outside the function or within other functions:https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Scope

- In computer programming, the scope of a name binding — an association of a name to an entity, such as a variable — is the part of a program where the name binding is valid, that is where the name can be used to refer to the entity. In other parts of the program the name may refer to a different entity (it may have a different binding), or to nothing at all (it may be unbound). The scope of a name binding is also known as the visibility of an entity, particularly in older or more technical literature — this is from the perspective of the referenced entity, not the referencing name:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scope_(computer_science)

Advantages of utilizing scope

Security: Adds security by ensuring variables can only be access by pre-defined parts of our program.Reduced Variable Name Collisions: Restricts re-using variable names; helps prevent overwriting variable names.

Lexical Scope

Lexical scope is the ability of the inner function to access the outer scope in which it is defined.

Lexing Time: When you run a piece of JS code that is parsed before it is run.- Lexical environment is a place where variables and functions live during the program execution.

Different Variables in JavaScript

- A variable always evaluates to the value it contains no matter how you declare it.

The different ways to declare variables

let: can be re-assigned; block-scoped.const: no re-assignment; block scoped.var: May or may not be re-assigned; scoped to a function.

Hoisting and Scoping with Variables

Hoisting is a JavaScript mechanism where

variables and function declarations are moved to the top of their scope before code execution.

!!!Only function declarations are hoisted in JavaScript, function expressions are not hoisted!!!

&&

!!! Only variables declared with var are hoisted!!!!

Slightly modified excerpt from:

source : https://ui.dev/ultimate-guide-to-execution-contexts-hoisting-scopes-and-closures-in-javascript/

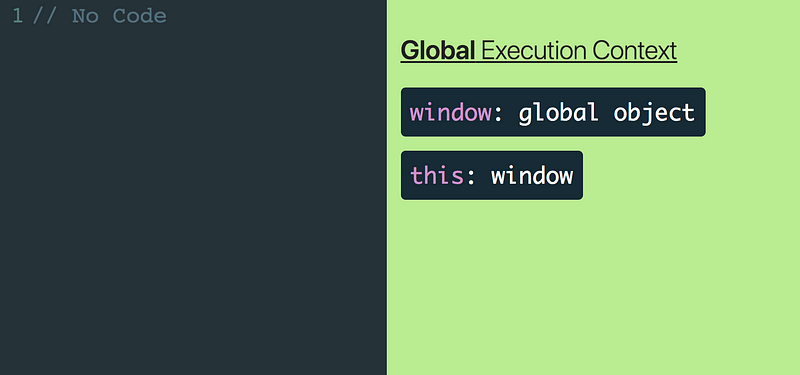

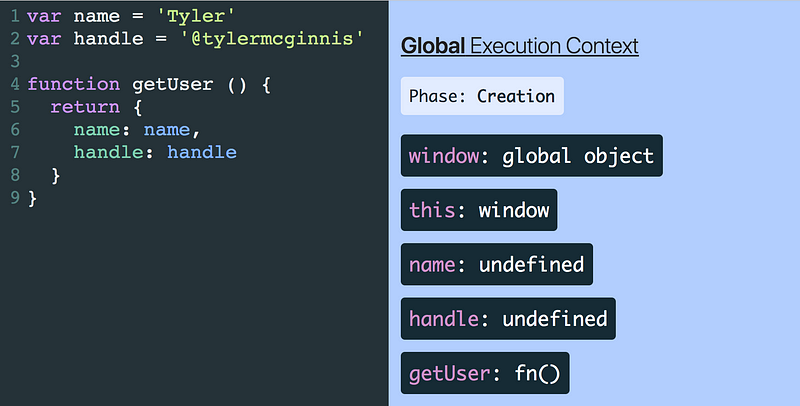

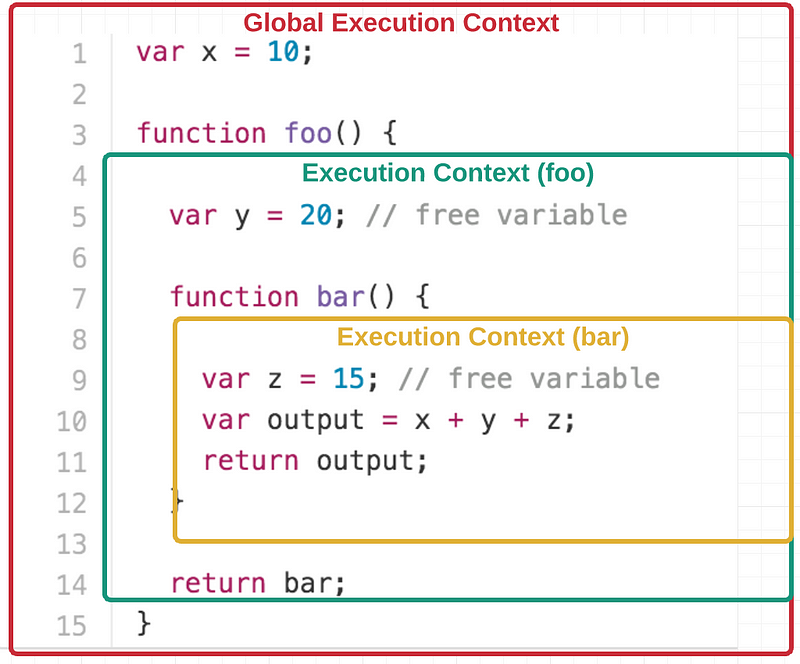

The first Execution Context ( a word that we don’t have to worry about the exact meaning of yet) that gets created when the JavaScript engine runs your code is called the “Global Execution Context”.

Initially this Execution Context will consist of two things —

- a global object

and

- a variable

called

this.

By default thethiskeyword will act as a reference to global object which will bewindowif you’re running JavaScript in the browser orglobalif you’re running it in a Node environment.

REMEMBER:

Node: this references a global object called

window (like the window that comprises the

content of a tab in chrome)

Browsers:this references a global object called

global

Above we can see that even without any

code, the Global Execution Context will still consist of two things — window and this. This is the Global Execution Context in its most basic

form.

Let’s step things up and see what happens when we start actually adding code to our program. Let’s start with adding a few variables.

The key take away is that

each Execution Context has two separate phases, a Creation phase and an Execution phase and each phase has its own unique

responsibilities.

Exaction Context:

Execution Context ≠(NOT EQUAL)≠≠≠Scope

- The global execution context is created before any code is executed.

- Whenever a function is executed invoked (this means the function is told to run… i.e. after the doSomething function has been declared … calling ‘doSomething()’, a new execution context gets created.

- Every execution context provides

thiskeyword, which points to an object to which the current code that’s being executed belongs.

For more info read about Event Queue and Call Stack

More formal definition from: Misa Ogura’s article on the subject

In JavaScript, execution context is an abstract concept that holds information about the environment within which the current code is being executed.

Remember: the JavaScript engine creates the global execution context before it starts to execute any code. From that point on, a new execution context gets created every time a function is executed, as the engine parses through your code. In fact, the global execution context is nothing special. It’s just like any other execution context, except that it gets created by default.

In the Global Creation phase, the JavaScript engine will

- Create a global object.

- Create an object called “this”.

- Set up memory space for variables and functions.

- Assign variable declarations a default value of “undefined” while placing any function declarations in memory.

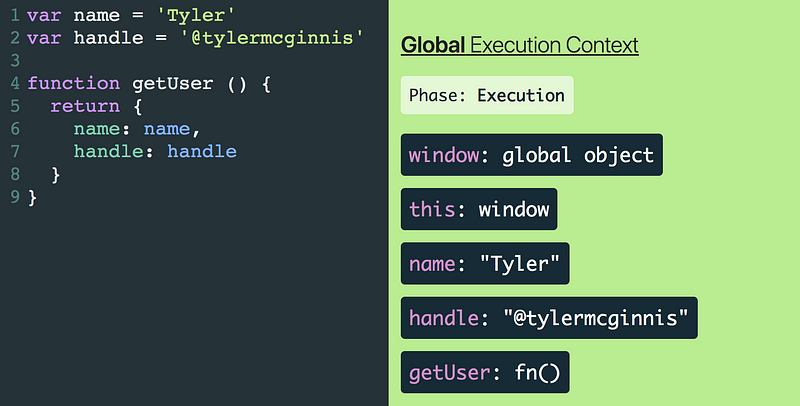

It’s not until the Execution phase where the JavaScript engine starts running your code line

by line and executing it.

We can see this flow from Creation phase to Execution phase in the GIF below. 🠗🠗🠗🠗🠗🠗

During the Creation phase:

The JavaScript engine said ‘let there be window and this‘

and there waswindowandthis… and it was good

Once the window and this are created;

Variable declarations are assigned a default

value of undefined

Any function declarations (getUser) are placed entirely into memory.

Exaction Phase:

Then once we enter the Execution phase, the JavaScript engine starts executing the

code line by line and assigns the real values to the variables already living in memory.

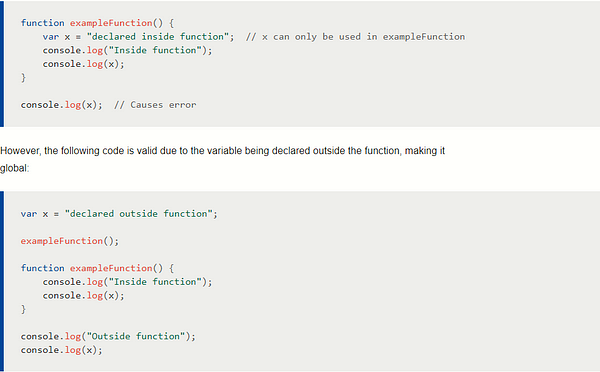

Function-Scoped Variables

Function scope means that parameters and variables defined in a function are visible everywhere within the function, but are not visible outside of the function.

Consider the next function that auto-executes, called IIFE.

(function autoexecute() {

let x = 1;

})();console.log(x);

//Uncaught ReferenceError: x is not definedIIFE stands for Immediately Invoked Function Expression and is a function that runs immediately after its definition.

Variables declared with var have only function scope. Even more, variables declared

with var are hoisted to the top of their scope. This way

they can be accessed before being declared. Take a look at the code below:

function doSomething(){

console.log(x);

var x = 1;

}doSomething(); //undefinedThis does not happen for let. A variable declared with let can be accessed only after its definition.

function doSomething(){

console.log(x);

let x = 1;

}doSomething();

//Uncaught ReferenceError: x is not definedA variable declared with var can be re-declared multiple times in the same scope. The

following code is just fine:

function doSomething(){

var x = 1

var x = 2;

console.log(x);

}doSomething();Variables declared with let or const

cannot be re-declared in the same scope:

function doSomething(){

let x = 1

let x = 2;

}

//Uncaught SyntaxError: Identifier 'x' has already been declaredMaybe we don’t even have to care about this,

as var has started to become obsolete.

- Only the var keyword creates function-scoped variables (however a var declared variable may be globally scoped if it is declared outside of a nested function in the global scope), this means our declared var keyword variable will be confined to the scope of our current function.

Why you shouldn’t use var:

- No error is thrown if you declare the same variable twice using var (conversely, both let and const will throw an error if a variable is declared twice)

- Variables declared with var are not block scoped (although they are function scoped), while with let and const they are. This is important because what’s the point of block scoping if you’re not going to use it. So using var in this context would require a situation in which a variable declared inside a function would need to be used in the global scope. I’m not able to think of any situations where that would be absolutely necessary, but perhaps they exist.

REMEMBER:

Var===🗑🚮👎🏽🤮

Also on a more serious note… if you have var in your projects in 2021 …hiring managers who peek at your projects to see your code quality will assume it was copy pasted from someone else’s legacy code circa 2014.

Hoisting with function-scoped variables

function test() {

// var hoistedVar;

console.log(hoistedVar); // => undefined

var hoistedVar = 10;

}

- Even though we initially declared & initialized our variable underneath the console.log var variables are “hoisted” to the top, but only in declaration (default value undefined until the exaction arrives at the line on which it was initialized.

Scope Spaced Repetition:

Scope is defined as which variables we

currently have access to and where. So far in this course, we have mostly been working in global scope, in that we can access any variable we have

created, anywhere in our code. There are a couple different levels of scope: block level scope is used in if statements and for loops. In block level scope, a variable declared using either let or const

is only available within the statement or loop (like i in

a for loop). Similarly, there is function scope, where

temperature exists inside the function, but not elsewhere

in your code file.

More on hoisting:

source: Hoisting in Modern JavaScript — let, const, and var

helloWorld(); // prints 'Hello World!' to the consolefunction helloWorld(){

console.log('Hello World!');

}

Function declarations are added to the memory during the compile stage, so we are able to access it in our code before the actual function declaration

When the JavaScript engine encounters a call to

helloWorld(), it will look into the lexical environment,

finds the function and will be able to execute it.

Hoisting Function Expressions

Only function declarations are hoisted in JavaScript, function expressions are not hoisted. For example: this code won’t work.

helloWorld(); // TypeError: helloWorld is not a functionvar helloWorld = function(){

console.log('Hello World!');

}

As JavaScript only hoist declarations, not

initializations (assignments), so the helloWorld will be

treated as a variable, not as a function. Because helloWorld is a var variable, so the engine will assign is the undefined value during hoisting.

So this code will work.

var helloWorld = function(){

console.log('Hello World!'); prints 'Hello World!'

}helloWorld();

Hoisting var variables:

Let’s look at some examples to understand

hoisting in case of var variables.

console.log(a); // outputs 'undefined'

var a = 3;

We expected 3 but instead got undefined. Why?

Remember JavaScript only hoist declarations, not initializations. That is, during compile time, JavaScript only stores function and variable declarations in the memory, not their assignments (value).

But why undefined?

When JavaScript engine finds a var variable declaration during the compile phase, it will

add that variable to the lexical environment and initialize it with undefined and later during the execution when it reaches the

line where the actual assignment is done in the code, it will assign that value to the variable.

https://codeburst.io/js-demystified-03-scope-f841ecad5c23 is a really great article… skip down to Hoisting and Scope to pursue this topic further!

Block-Scoped Variables

Things that create block-scopes:

- If Statements

- While Loops

- Switch Statements

- For Loops

- Curly Boiz ‘{}’ ….. anything between cury brackets is scoped to within those brackets.

Properties of Const declared variables:

- They are block-scoped like let.

- JS will enforce constants by raising an error if you try to change them.

- Constants that are assigned to Reference Types are mutable

Hoisting with block-scoped variables

- Unlike vars in function scopes,

- let and const in their block scopes do not get their declarations hoisted.

- Instead they are not initialized until their definitions are evaluated instead of undefined we will get an error.

Temporal Dead Zone: The time before a let or const variable is declared.

Function Scope vs Block Scope

- The downside of the flexibility of var is that it can easily overwrite previously declared variables.

- The block-scope limitations of let and const were introduced to easily avoid accidentally overwriting variable values.

Global Variables

- Any variables declared without a

declaration term will be considered

global scope. - Every time a variable is declared on the global scope, the change of collision increases.

- Use the proper declarations to manage your code: Avoid being a sloppy programmer!

Variables defined outside any function, block, or module scope have global scope. Variables in global scope can be accessed from everywhere in the application.

When a module system is enabled it’s harder to make global variables, but one can still do it. By defining a variable in HTML, outside any function, a global variable can be created:

When there is no module system in place, it is a lot easier to create global variables. A variable declared outside any function, in any file, is a global variable.

Global variables are available for the lifetime of the application.

Another way for creating a global variable is to

use the window global object anywhere in the application:

window.GLOBAL_DATA = { value: 1 };At this point, the GLOBAL_DATA variable is visible everywhere.

console.log(GLOBAL_DATA)As you can imagine these practices are bad practices.

*Module scope

Before modules, a variable declared outside any function was a global variable. In modules, a variable declared outside any function is hidden and not available to other modules unless it is explicitly exported.

Exporting makes a function or object available

to other modules. In the next example, I export a function from the sequence.js module file:

// in sequence.js

export { sequence, toList, take };Importing makes a function or object, from other modules, available to the current module.

import { sequence, toList, toList } from "./sequence";In a way, we can imagine a module as a self-executing function that takes the import data as inputs and returns the export data.

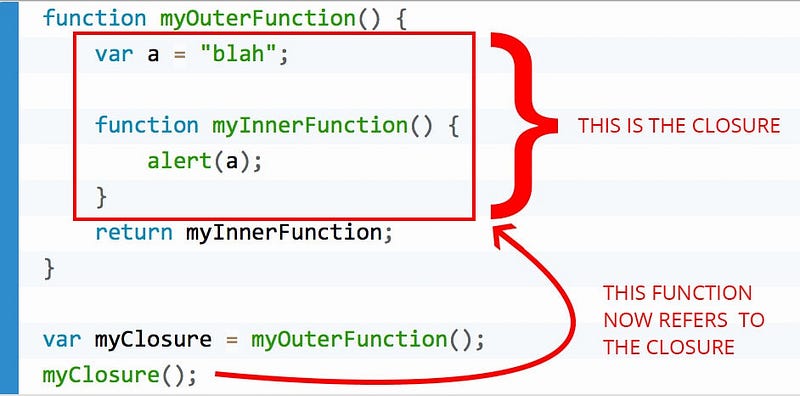

Closures

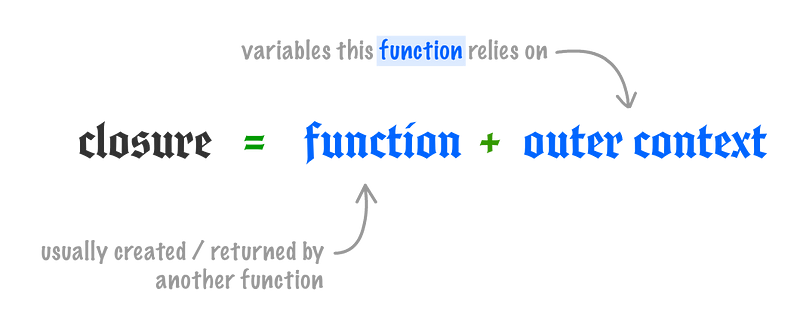

- Closure : The combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function is declared.

- Use : A closure is when an inner function uses, or changes, variables in an outer function.

- Very important for creativity, flexibility, and security of your code.

Lexical Environment: Consists of any variables available within the scope in which a closure was declared (local inner, outer, and global).

Closures and Scope

Basic Closure Rules:

- Closures have access to all variables in it’s lexical environment.

- A closure will keep reference to all the variables when it was defined even if the outer function has returned.

Applications of Closures

- Private State

- JS does not have a way of declaring a function as exclusively private, however we can use closures to make a private state.

- Passing Arguments Implicitly

- We can use closures to pass down arguments to helper functions.

OVERVIEW

Let’s look at the Window/Console in a

browser/node environment. Type window to your chrome

console. JavaScript is executed in this context, also known as the global scope.

There are two types of scope in javascript,

Global Vs. Local and that this is important to understand

in terms of a computer program written in JavaScript.

When a function is declared and created, a new

scope is also created. Any variables declared within that

function's scope will be enclosed in a

lexical/private scope that belongs to that function. Also, it is important to remember that functions look

outward for context. If some variable isn't defined

in a function's scope, the function will look outside the scope chain and search for a variable being

referenced in the outer scope. This is what closure is all about.

In it’s most simplest of forms this is a closure:

const foo = 'bar';

function returnFoo () {

return foo;

}

returnFoo();

// -> reaches outside its scope to find foo because it doesn't exist inside of return Foo's scope when foo is referenced.The function body (code inside returnFoo) has access to the outside scope (code outside of returnFoo) and can access that ‘foo’ variable.

Let’s look at another example:

const lastName = 'Bob';

function greet() {

const firstName = 'Jim';

alert(`The name's ${lastName}, ${firstName} ${lastName}`);

}

console.log(lastName);Not much different than the idea presented

above, but the thought remains the same. When ‘greet’ is called, it has no context in its local scope of

finding lastName so, it looks outside its scope to find

it and use the lastName that is found there.

Let’s take this a step further. In the given

examples, we’ve seen that we have created two environments for our code. The first would be the global

environment where lastName and greet exist. The second would be the local environment where

the alert function is called. Let's represent those two environments like this:

What is a closure?

A closure is an inner function that has access to the outer (enclosing) function’s variables — scope chain. The closure has three scope chains: it has access to its own scope (variables defined between its curly brackets), it has access to the outer function’s variables, and it has access to the global variables.

The inner function has access not only to the outer function’s variables, but also to the outer function’s parameters. Note that the inner function cannot call the outer function’s arguments object, however, even though it can call the outer function’s parameters directly.

You create a closure by adding a function inside another function.

A Basic Example:

Scope chain

Every scope has a link to the parent scope. When a variable is used, JavaScript looks down the scope chain until it either finds the requested variable or until it reaches the global scope, which is the end of the scope chain.

Context in JavaScript

Scope: Refers to the visibility and availability of variables.Context: Refers to the value of thethiskeyword when code is executed.

Every function invocation has both a scope and

a context. Even though technically functions are objects in JS, you can think of scope as pertaining to

functions in which a variable was defined, and context as the object on which some variable or method

(function) may exist. Scope describes a function has access to when it is invoked (unique to each

invocation). Context is always the value of the this

keyword which in turn is a reference to the object that a piece of code exists within.

Context is most often determined by how a

function is invoked. When a function is called as a method of an object, this is set to the object the method is called on:

this ?

This: Keyword that exists in every function and evaluates to the object that is currently invoking that function.- Method-Style Invocation : syntax goes like

object.method(arg). (i.e. array.push, str.toUpperCase() Contextrefers to the value of this within a function andthisrefers to where a function is invoked.

Issues with Scope and Context

- If

thisis called using normal function style invocation, our output will be the contents of the global object.

When Methods have an Unexpected Context

- In the above example we get undefined when we assign our this function to a variable bc there is no obj to reference except the global one!

Strictly Protecting the Global Object

We can run JS in strict mode by tagging use strict at the top of our program.

- If we try to invoke this on our global function in strict mode we will no longer be able to access it and instead just get undefined.

Changing Context using Bind

“The simplest use of

bind() is to make a function that, no matter

how it is called, is called with a particular this value".

Binding with Arguments

- We can also use bind() to bind arguments to a function.

Arrow Functions (Fat Arrows)

side note … if you don’t know what this means ignore it… but if you write an arrow function that utilizes an implicit return… that’s roughly equivalent to what is referred to as a lambda function in other languages.

=>: A more concise way of declaring a function and also considers the behavior ofthisand context.

Arrow Functions Solving Problems

As you can see the arrow function is shorter and easier to read.

Anatomy of an Arrow Function

- If there is only a single parameter there is no need to add parenthesis before the arrow function.

- However if there are zero parameters then you must add an empty set of parentheses.

Single Expression Arrow Functions

- Arrow functions, unlike normal functions, carry over context, binding

thislexically. - Value of

thisinside an arrow function is not dependent on how it is invoked. - Because arrow functions

already have a bound context, you can’t reassign

this.

Phewh… that’s a lot… let’s go over some of that again!

Block Scope Review:

Block scope is defined with curly braces. It is

separated by { and }.

Variables declared with let and const can have block scope. They can only be accessed in the

block in which they are defined.

Consider the next code that emphasizes let block scope:

let x = 1;

{

let x = 2;

}

console.log(x); //1In contrast, the var declaration has no block scope:

var x = 1;

{

var x = 2;

}

console.log(x); //2Closures Spaced Repetition

1. Closures have access to the outer function’s variable even after the outer function returns:

One of the most important features with closures is that the inner function still has access to the outer function’s variables even after the outer function has returned.

When functions in JavaScript execute, they use the same scope chain that was in effect when they were created.

This means that even after the outer function has returned, the inner function still has access to the outer function’s variables. Therefore, you can call the inner function later in your program.

See here:

2. Closures store references to the outer function’s variables:

They do not store the actual value.

Closures get more interesting when the value of the outer function’s variable changes before the closure is called.

And this powerful feature can be harnessed in creative ways…namely private variables.

3. Closures Gone Bad

Because closures have access to the updated values of the outer function’s variables, they can also lead to bugs when the outer function’s variable changes with a for loop.

For example:

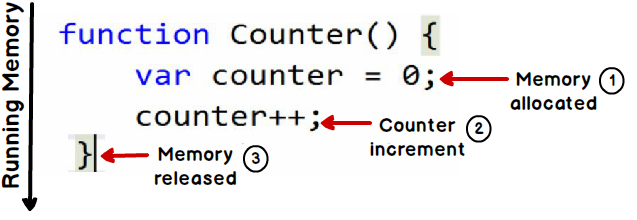

Cclosure is a word we use to refer to the context of a given function. Normally our function starts from scratch every time we run it.

However, if we were to return a function from

addOne() that referenced counter, counter would become part of the context of that new

function, even after addOne() finishes executing. This is

easier to see in code than to explain in words:

This works! we only instantiate counter

when createAdder() is called, but it's value gets

updated whenever the function it returns is called.

We say that this inner

function is closed around the variable counter

Definition: (According to MDN) A closure is the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared.

Global Scope Spaced Repetition:

Scope in JavaScript works like it does in most languages. If something is defined at the root level, that’s global scope — we can access (and modify) that variable from anywhere. If it’s a function we defined, we can call it from anywhere.

The Problem with Global Scope

So it seems we should declare all of our variables at the global scope.

Why could this be a problem?

It seems reasonable to want counter to only be

accessed/modified through our addOne() function, but if

our variable is defined within the global scope, it's simply not so.

This may not seem like a major concern — we can just make sure we don’t access it directly.

We need some form of encapsulation — i.e. the data our function relies on is completely contained within the logic of that function

Inner Scope

OK, this seems to work as expected, however

What about inside of our addOne() function?

Every function creates it’s own local scope.

Compared to it’s context (i.e. where our function is defined), we call this the inner scope

Our function can access/modify anything outside

of it’s scope, so the body of our function, { counter++;

}, has an effect that persists in the outside scope.

What about the other way around…Can global scope modify inner scope?

Because counter is defined

within our function's scope, it doesn't exist within the global scope, so referencing it there

doesn't make sense.

Context vs. Scope

The first important thing to clear up is that context and scope are not the same. I have noticed many developers over the years often confuse the two terms (myself included), incorrectly describing one for the other.

Every function invocation has both a scope and a context associated with it.

To condense it down to a single concept, scope is function-based while context is object-based.

In other words, scope pertains to the variable

access of a function when it is invoked and is unique to each invocation. Context is always the value of

the this keyword which is a reference to the object that

"owns" the currently executing code.

Variable Scope

A variable can be defined in either local or global scope, which establishes the variables’ accessibility from different scopes during runtime.

Local variables exist only within the function body of which they are defined and will have a different scope for every call of that function. There it is subject for value assignment, retrieval, and manipulation only within that call and is not accessible outside of that scope.

ECMAScript 6 (ES6/ES2015) introduced the let and const keywords that support the declaration of block scope

local variables.

This means the variable will be confined to the

scope of a block that it is defined in, such as an if

statement or for loop and will not be accessible outside

of the opening and closing curly braces of the block.

This is contrary to var declarations which are accessible outside blocks they are

defined in.

The difference between let and const is that a const declaration is, as the name implies, constant - a

read-only reference to a value.

This does not mean the value is immutable, just that the variable identifier cannot be reassigned.

Closure Spaced Repetition:

recall:

Lexical scope is the ability for a function scope to access variables from the parent scope. We call the child function to be lexically bound by that of the parent function.

AND

A lexical environment is an abstraction that holds identifier-variable mapping. Identifier refers to the name of variables/functions, and the variable is the reference to actual object [including function object] or primitive value.

This is similar to an object with a method on it…

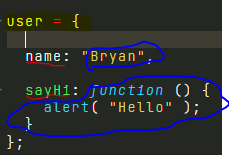

In the picture below… sayHi (and name) are identifiers and the function and (string “bryan”) are variable values.

Accessing variables outside of the immediate lexical scope creates a closure.

A closure is to put it simply, when a nested function is defined inside of another function gains access to the outer functions variables.

Returning the nested function from the ‘parent function’ that enclosed the nested function definition, allows you to maintain access to the local variables, (arguments, and potentially even more inner function declarations) of its outer function… without exposing the variables or arguments of outer function…. to any of the other functions that were not declared inside of it.

What is “this” Context

Context is most often determined by how a function is invoked.

When a function is called as a method of an

object, this is set to the object the method is called

on:

The same principle applies when invoking a

function with the new operator to create an instance of

an object.

When invoked in this manner, the value of this within the scope of the function will be set to the

newly created instance:

When called as an unbound function, this will default to the global context or window object in

the browser. However, if the function is executed in strict mode,

the context will default to undefined.

Execution Context Spaced Repetition:

JavaScript is a single threaded language, meaning only one task can be executed at a time. When the JavaScript interpreter initially executes code, it first enters into a global execution context by default. Each invocation of a function from this point on will result in the creation of a new execution context.

This is where confusion often sets in, the term “execution context” is actually for all intents and purposes referring more to scope and not context.

It is an unfortunate naming convention, however it is the terminology as defined by the ECMAScript specification, so we’re kind of stuck with it.

Each time a new execution context is created it is appended to the top of the execution stack (call stack).

The browser will always execute the current execution context that is atop the execution stack. Once completed, it will be removed from the top of the stack and control will return to the execution context below.

An execution context can be divided into a creation and execution phase. In the creation phase, the interpreter will first create a variable object that is composed of all the variables, function declarations, and arguments defined inside the execution context.

From there the scope chain is initialized next, and the value of this is determined last. Then in the execution phase, code is

interpreted and executed.

Resources

Dmitry Soshnikov, Javascript:Core

Conclusion

Variables defined in global scope are available everywhere in the application.

In a module, a variable declared outside any function is hidden and not available to other modules unless it is explicitly exported.

Function scope means that parameters and variables defined in a function are visible everywhere within the function

Variables declared with let and const have block scope. var doesn’t have block scope.

Comments

Post a Comment

Share your thoughts!